Author Archives: agobost

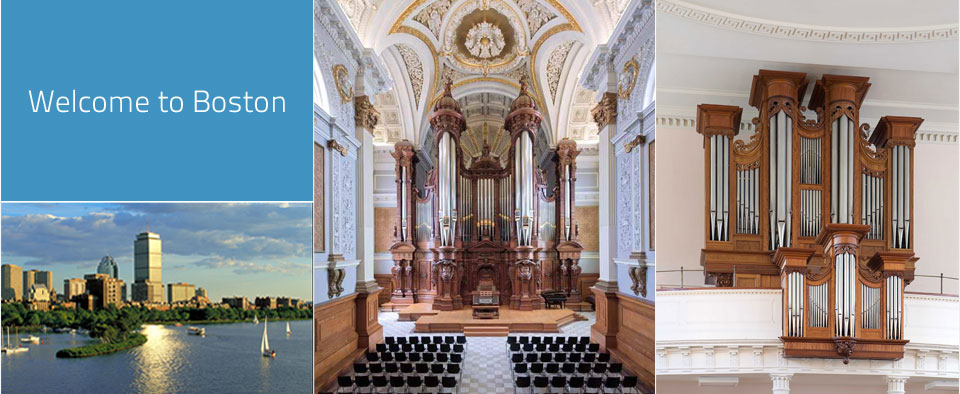

Cathedral of the Holy Cross

At 364 feet long, ninety feet wide, and 120 feet high, with a seating capacity of 1,700, Holy Cross Cathedral is New England’s largest church. Dedicated in December 1875, it was built of locally quarried Roxbury puddingstone and Quincy granite to designs of noted ecclesiastical architect Patrick C. Keely. The advent of cast-iron construction permitted exceptionally slender nave columns supporting the largest wooden vault of its time. An unfashionably remote location—the former site of the town gallows—betrays Anglo-Saxon Protestant Boston’s ambivalence toward waves of “foreign” immigrants, for whom the new cathedral’s completion after nine years of construction was a signal achievement.

The 1875 Hook & Hastings wasn’t the largest organ built in the United States during the nineteenth century, but at seventy voices and 101 ranks it is the biggest to have survived unscathed. Built in the early years after Francis Hastings assumed control of the firm from founding brothers Elias and George Hook, Holy Cross’s instrument was the first of several organs intended to generate considerable power in vast spaces. Fully a quarter of the organ’s resources—twenty-seven ranks—are vested in a blazing Great chorus topped by a Trumpet and Clarion imported from France. With a five-rank cornet in every department, many registers of pure tin, and a ten-inch pressure Tuba built and voiced in the Hook & Hastings shop, here was Hastings’ manifesto on post-Civil War tonal heroism.

Like the neighborhood itself, Opus 801 languished into the twentieth century and into the shadows of newer, “better” organs with electric action and French horns. In the 1920s, the organ was casually electrified and fitted with a second-hand theatre organ console. The Hook revival of the 1960s and ’70s brought renewed attention, however. More recently, under the tireless banner-waving of Cathedral organist Leo Abbott, the instrument is seeing happier days. In 2003, Andover Organ Company supplied a modern console patterned after the original, and in the past decade has undertaken select restoration as funding has become available.

St. Paul, Cambridge

The steady influx of Catholics into Protestant Cambridge led to the retrofitting of a disused Congregational church by 1873, followed by the present building of 1915–1923 to plans of Edward Graham, heavily indebted to Verona’s Romanesque masterpiece, San Zeno Maggiore. A bell in the elegantly slender campanile bears a wistful inscription from Isaiah: “Vox clamantis in deserto”—a Catholic voice crying out in the hard Protestant wilderness that is Harvard Square. Since 1963, Saint Paul’s has been home to a boy-choir school whose ensembles sing daily offices in a sumptuous acoustic—one which, alas, has never been graced with a purpose-built, entirely new organ. Jesse Woodbury’s Opus 251 of 1904 was enlarged, electrified, and installed in the gallery in 1924 by local organ builder Paul Mias. Casavant supplied a new console in 1947, then, in 1959, a two-manual unenclosed section in the south transept. Among the area’s first Casavants from tonal director Lawrence Phelps, it mirrored the aspirations of the day right down to a bee-in-a-bedpan sixteen-foot Krummhorn (since removed). More recent work falls under the banner of renovation: tonal changes in the 1970s by Arthur Birchall; a new, Aeolian-Skinner-style console in 1999 by Robert Turner; and a constipation of digital voices, including the entire Chancel Swell.

Chancel Organ: Casavant Frères, 1959 Digital additions and new console, 1999

St. Joseph Church

Long before the term “white flight” entered the language, white Bostonians spent an inordinate amount of time fleeing one another. Saint Joseph’s survival bears witness to two tumultuous periods in the city’s history. Built for Congregationalists in 1834 by Alexander Parris, Boston’s leading architect after Charles Bullfinch departed for Washington to complete the U.S. Capitol, the church briefly attracted its intended constituency. By 1862, however, the West End was largely Irish Catholic, prompting a sale to the archdiocese. Successive waves of immigration brought Eastern European Jews, Armenians, Greeks, and Syrians to Boston’s most diverse melting pot. Government authorities in search of a higher tax base declared the solid working-class quarter a slum in 1953, leveling forty-six acres and displacing 2,700 families, few of whom could afford to return to unsightly new high-rises. Happily untouchable as a church, Saint Joseph’s regained its vibrancy to stand as a lonely reminder of a vanished neighborhood.

The 1883 Hook & Hastings is an excellent example of how that company matured into a manufacturing powerhouse while retaining remarkable quality. If the stoplist for Opus 1168 is not exactly typical of two-manuals, with such big-organ luxuries as a Great sixteen foot and three Swell four-foot stops, the tight choruses, polished delicacy, and excellent reeds are. They bear witness to Hook & Hastings’ enviable quality and consistency in this period.

.

Old West Church

Occupying higher ground than Old North Church, the original church of 1737 was razed by British troops fearful its spire would also be used to send signals across the river. Not until 1806 did Benjamin Asher complete the present Federal-style building. Together with the eighteenth-century Otis House next door, Old West is a rare survivor of the West End neighborhood that vanished during Boston’s 1960s brush with urban renewal. The proportions of the front tower are especially harmonious, shallow pilasters leading the eye upward to two floors of windows surmounted by clock, swag, and cupola. Congregationalist at its founding, converted into a public library at the end of the nineteenth century, Old West has housed a Methodist congregation since 1964.

The 1971 Fisk organ finds that builder at his most intense and concentrated. Rarely has such a wide musical reach been distilled into a mere twenty-nine stops: choruses on all departments, tierce stops on each manual, reeds for early French repertoire alongside an embryonic Romantic Swell, all from a compact, detached keydesk. Cunning treatment of the voices allows them to be coaxed this way for German music, that way for French. Old West has taught a generation of organists about sensitive key action and elegantly flexible wind. The early nineteenth-century upper case is recycled from an Appleton organ, widened from three to four towers in homage to Father Smith; the chair case was built new to match.

St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church

The first Saint Andrew’s was a small chapel built and dedicated in 1894, expanded in 1921 and again in 1931. A parish house arrived in the late 1940s, and in the 1950s the sanctuary was enlarged together with a new education wing. The first organ was a ten-rank Wicks of injudicious unification. When Donald Teeters arrived in 1957, he began a slow campaign for a new organ. Eventually, Donald Willing, one of the era’s prominent writers and thinkers on organ design, was brought in as adviser (at the time, he was organist at Wellesley Congregational Church down the road), and the commission was entrusted to Casavant Frères, under the tonal direction of Lawrence Phelps and supervised by Karl Wilhelm. The new instrument was dedicated in February 1965.

The church’s previous organist, J. Harrison Kelton, is responsible for the new organ, which, when completed in 2006, was Juget-Sinclair’s largest work to date. While some acoustical improvements have been made in the chancel and crossing (really more of a sharp left turn from nave to chapel), the room remains a stubbornly dry ring into which the builders decided to throw a thirty-four-stop raging bull. With its crisp, balanced mechanical key action, the centrally located detached console reaches leftward to the Great and right to the Swell, with Pedal on both sides. While not copying any particular organ, the tonal language here is decidedly French, particularly the bracing reeds, ringing tierce combinations, and roaring Pedal.

Old South Church in Boston

Originally known as New Old South Church (“new” being 1875), to distinguish it from still-standing Old South Meeting House (1729), this is the third home of a congregation gathered in 1669 that has counted Benjamin Franklin, William Dawes, and Samuel Adams among its members. Cummings & Sears adapted John Ruskin’s Venetian Gothic style to a corner lot in a masterful way, evoking hints of Basilica San Marco. In 1905, Louis Comfort Tiffany replaced the original interior stenciling with his own in purple and metallic silver, covering Clayton & Bell’s stained glass with purple glass, as well. That decorative scheme perished under a coat of battleship grey paint in the 1950s, followed by a skillful if muted approximation of the original interior in 1984. As if in sympathy with the collapse of San Marco’s campanile in 1902, Old South’s bell tower began listing by the 1920s and had to be pulled down and rebuilt slightly lower in 1937.

George Hutchings trained in the Hook factory, but when it became clear that Francis Hastings was to assume the reins, Hutchings set out on his own in 1869. His large three-manual in 1875 for the gallery of Old South showed just how quickly he brought his establishment up to speed, for here was an instrument comprehensive in both tone and mechanism, with Barker Levers alongside a free-reed Physharmonica. Behind the same case, Ernest Skinner installed his Opus 231 of 1915, retaining the east-end location for a Solo and thirty-two-foot Bourdon. With three thirty-two-foot voices, and larger than Skinner’s 1913 flagship at New York’s Saint Thomas Church, the Old South instrument was Skinner’s first truly large opus on home turf.

In 1969, ninety-three ranks of Reuter arrived, divided between gallery and chancel with consoles in both locations. The Skinner’s thirty-two-foot Violone and Bombarde were retained, the latter a leaden foundation under the Reuter’s lean, steely sound. The church decided to revert to Skinner after a dozen years, inspired by news that a large 1921 organ, similar in scope to Old South’s 1915 instrument, was about to be demolished along with its home, the Auditorium in Saint Paul, Minnesota. Saved from the wrecking ball, Skinner Opus 308 was brought to Massachusetts. A partnership of Casavant Frères and Hokans-Knapp took charge of the organ’s rebuilding and re-engineering. For the first time, all musical forces would be grouped at the east end with the clergy. Great and Pedal were installed behind the chancel screen, with Swell and Tuba Mirabilis stacked in the south tower, and Choir, Solo, and String in the north. The thirty-two-foot pipes are dotted about the landscape: Violone in the northeast, Bombarde in the southeast, Dulciana (ex-1915 Skinner Violone) in the south tower façade, wood Diapason in the west gallery. Nelson Barden undertook extensive rebuilding and tonal renovation from 1986 to 1990, using vintage Skinner pipework and new material from Austin and Schoenstein. In 1996, Austin supplied all-new Gallery manual pipework. With 115 ranks, this is Boston’s second-largest organ.

Casavant Frères, Ltée and Hokans-Knapp, Associates – 1982-1984, rebuilding and reconfiguration Nelson Barden Associates, Inc. – 1987-1990, rebuilding and tonal changes

The First Church of Christ, Scientist

The Mother Church and headquarters for Christian Science worldwide, The First Church of Christ, Scientist’s original Romanesque Revival building opened in 1894 on an unusual trapezoidal lot and was quickly outgrown; the adjacent Extension of 1904–1906 seats some 3,000. Architect Charles Brigham’s original Ottoman-inspired design was substantially altered by Solon Spencer Beman along classical Renaissance lines, dispensing with plans for corner towers and a minaret-cum-campanile. The result owes much to Venice’s Santa Maria della Salute. A belt of New Hampshire granite around the Extension’s base cleverly ties the two disparate buildings together. The 1934 publishing house building is home to the Mary Baker Eddy Library and its famous Mapparium. I.M. Pei & Partners, with Araldo Cossutta, fashioned the surrounding administrative buildings and reflecting pool in the early 1970s.

The three-manual Farrand & Votey organ for the original edifice comes from that builder’s five short years of existence, between 1893 and 1898. Some of its pipes were retained in Aeolian-Skinner’s otherwise new and fairly typical three-manual of 1951, Opus 1202. While the 1894 façade was retained, the organ itself was placed in the ceiling so as to increase space for the 235-rank organ next door in the Extension.

Aeolian-Skinner’s Opus 1203 is the largest single organ the firm ever built (to begin with, there are five Pedal mixtures). G. Donald Harrison and consultant Lawrence Phelps collaborated on the tonal design. Having worked for Aeolian-Skinner from 1944 to 1948, Phelps had spent a brief period with Walter Holtkamp before returning to Boston for this project. (Phelps’ wife, Ruth Barrett Arno Phelps, was the Mother Church organist.) The complex scheme includes four unenclosed departments, each with multiple-mixtured choruses and cornet voices, against three enclosed departments. The Solo lives apart from the rest, in a separate, elevated chamber speaking out of the circular grille at the upper left, where the original 1906 Hook-Hastings Echo had been located. Altered by Jason McKown and Jack Steinkampf in 1980 and 1981, the organ underwent a complete mechanical refurbishment by Foley-Baker, Inc. between 1997 and 2000. A now-aged Phelps returned to coordinate all work, including a few changes and additions. Tonal work was handled by Austin Organs, Inc. under the direction of David Broome and Daniel Kingman, the latter doing much of the on-site finishing.

The Basilica of Our Lady of Perpetual Help/Mission Church

Properly known as the Basilica and Shrine of Our Lady of Perpetual Help, Mission Church was erected between 1876 and 1878 of locally quarried Roxbury puddingstone and Quincy granite, its 215-foot towers not completed until 1910. Long associated with the Redemptorist Fathers’ missions to the disenfranchised, Mission Church is one of fifty-four minor basilicas in the U.S., entitled to its own coat of arms and a papal umbrellina, kept half-open to signify the Basilica’s readiness to host His Holiness at any moment. Alexandre Guilmant played the organ shortly after its installation.

Robert and Richard Lahaise – 1968, tonal and mechanical changes

Methuen Memorial Music Hall

Few organs thrown out of their original locations have landed as gracefully as Methuen’s. Installed in 1863 on the stage of the original Boston Music Hall, Walcker’s four-manual instrument was a showcase of novelty: pneumatic action, sliderless cone-valve windchests, two swell enclosures (including part of the Pedal), a plethora of curiously made flutes and free reeds, a crescendo device, and what would prove the first thirty-two-foot reed (free, not beating) heard on these shores. But as soon as 1881, the newly founded Boston Symphony Orchestra began jostling for space around the organ’s muscled herms, winning the turf battle in 1884. The instrument, which had cost $60,000, was sold for $5,000, removed to storage, and sold again for $1,500 to its savior, Edward Francis Searles.

To house the organ, Searles commissioned an Anglo-Dutch-style hall from Henry Vaughan, English-born architect of the National Cathedral. This great room served as Searles’ music salon from 1909 until his death, in 1920. From thence the property passed through the hands of Ernest M. Skinner, whose workshop it was until his bankruptcy, to a civic organization that has operated it as a cultural center since 1946.

At Methuen, the Treat Organ Company put the pipes on new slider chests and provided a terrace-jamb console, preserving Walcker’s original in-built keydesk with its colored porcelain indicators. During Skinner’s ownership of the hall and organ, a few tonal changes were made, but nothing so drastic as the renovation undertaken by Aeolian-Skinner in 1947. The mechanism was sped up, the console modernized, and almost half the pipes replaced to conform to the firm’s house style. In its first decade, the Andover Organ Institute, guided by Arthur Howes, brought the instrument to public notice and played an important role in shaping post-war organ reform thinking. Andover Organ Company, the organ’s curators for decades, installed a Great reed chorus in 1971; more recently they have again updated the console, moved Aeolian-Skinner’s spiky Krummhorn from Choir to Positiv, and installed a smoother clarinet in its place. Regular summer Wednesday recitals are supplemented by special events throughout the year.

.

Aeolian-Skinner Organ Company, Inc., Opus 1103, 1947